83%.

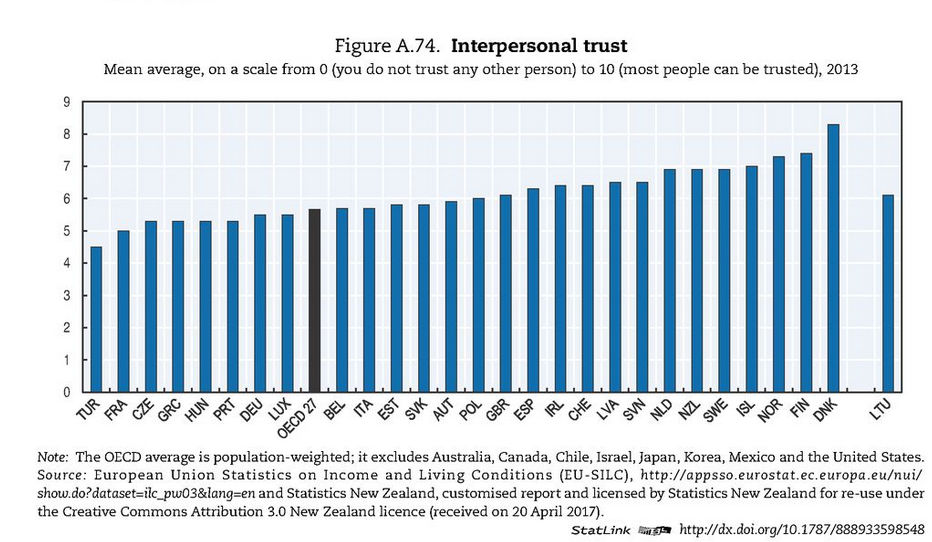

“Can most people be trusted?”. If you ask the Danes, they will answer yes 8.3 times out of 10, on average. This makes them the most trusting population in the world according to the OECD 2017 “How’s life” annual survey.

The probably complex historical and social context that has led to this state of affairs, the question whether the population’s homogeneity is a factor, or whether the Danes are simply too lazy to mistrust other people… will not be the subject of this article.

Nor will we address the question of whether the record high tax pressure is a prerequisite for the welfare society and a high trust score. Nor, conversely, whether the high trust level simply makes society so extraordinarily efficient that it can accommodate a large and inefficient public sector as well as a largely sub-optimal allocation of resources to tasks on a societal level, in part compensated for by undeclared work (which 40% of Danes make use of), not to mention widespread crab mentality.

This article is specifically about how – and why – we construct trust at The Danish-French School of Copenhagen.

First we will consider the importance of the main tool that we are using – relationships and the approx. 17 practical principles we use to build them. They are summarized later in the next section, but might be worthwhile a read to better understand the article.

Then we will apply an information-theoretic perspective to each of the principles in order to illustrate how the process of reducing the amount of information addresses a fundamental need, in turn strengthening relations and trust.

Finally we present a simple model that illustrates why trust deserves a very particular focus as a value in society.

Relationships and information condensation

Trust is about relations between people, hence the most important of our 17 principles, “Establish relationships”.

An important aspect that has turned out to be recurring in many of the 17 principles is the overarching idea of information reduction, or rather information condensation. The brain continuously processes enormous amounts of information and the task it accomplishes when distinguishing relevant from irrelevant – condensing the information – is a truly formidable effort. We see it as a sort of extra layer at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: the ability to give oneself a direction in the super-high-dimensional space of potentialities conveyed by our senses, but in essence akin to what the simplest organisms must be experiencing when following say a nutrient gradient.

From a didactical and a relationship-building perspective this also means that whenever one can help the child “find the gradient”, it is a fundamental need that is being addressed, resulting in a significant strengthening of the relationship and the trust.

This information-theoretic perspective sheds a new light on each of the 17 principles:

| Principle | How the principle acts as information condensing | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Establish relationships |

|

| 2 | Agreements | A clear and condensed formulation of what to expect. |

| 3 | Rules, recognizing justice and co-ownership | Like in principle no. 2 but even more condensed. Also, fairness and justice imply a high degree of predictability. |

| 4 | Noise and quiet | Clearly distinguish the information-carrying signals from the noise. |

| 5 | Simple explanations | Information-dense nuggets. |

| 6 | High expectations | A clear gradient to follow- which probably explains why they are so efficient. |

| 7 | Help others – social capital | Supports in building relations, see principle no. 1. |

| 8 | Keep track of what the individual is doing / finishing things | Staying focused on a gradient. |

| 9 | Children need to test | Clarifying the limits of the playing field. |

| 10 | Repetition makes master | Repetition is probably the most common information-condensing mechanism. |

| 11 | Set limits to the tasks, not the time spent | Staying focused on a gradient. |

| 12 | Give options | Reducing the high-dimensional space of possibilities to a few options. |

| 13 | Correct mistakes as early as possible – give and demand feedback | Feedback condenses the vast “what-I-might-have-been-perceived-like” to the simple “what-actually-was”. |

| 14 | Do not steal the children’s play | Favors relations, see principle 1. |

| 15 | Avoid “Shh!” and instead give specific messages | Specific messages are obviously much more information-dense and actionable. |

| 16 | Only one adult at a time | One responsible adult creates a simpler field of expectations than multiple persons. |

| 17 | Clear communication and honesty | Should be self-explanatory. |

And so it appears that information condensation is indeed a governing trait of our pedagogy.

A few aspects that are not covered by the 17 principles, but are relevant in a trust-building context:

Long-lasting relations

The multi-aged structure of the school favors long-lasting relationships. Our teachers typically follow the children for many years – potentially from when they are 2 to 15. This means that teachers and children can get to know each other very well, simply due to the sheer time they spend together. But it also means that all the group members are in it for the long run, further strengthening the incentives to construct strong relations.

Impediments to trust

A direct impediment to trust typically occurs when the members of the group need to compete for a scarce resource, be it two children wanting the same toy, or two employees wanting the same job, etc. The guiding principles we have successfully applied in those cases were:

- share the resource, for instance taking turns. Very often it will from a global perspective be a better solution that the two members each get ~50% of the resource, rather than splitting 0% – 100%.

- in case the resource is not shareable, allocate the resource according to what is most aligned with the group’s mission. Discuss what best serves the greater purpose and apply that. Sometimes you just need to take one for the team.

- in either case, be conscious of and open about the conflict. When the solution is fair, it is much easier to accept it even if it is not at one’s own advantage.

Another impediment to trust stems from the average human being’s relative perception of success. When you sit in a train and the train next to you starts moving, you can get the impression that you are moving backwards. That is similar to when your friend has success and you feel it as your failure. Both impressions are factually wrong, resulting from a flaw in how our perception works. Suffice to imagine that you are seeing the situations from an absolute observer position and it becomes clear that your friend’s success is in part your success, and that the winning strategy is to help your friends, to energize your network. We teach that from an early age.

The why

We have covered the question of how we construct trust at the school. The reason why should become very clear when considering the following model:

Given some relatively obvious assumptions of a somewhat mathematical nature, we will conclude that it is worthwhile to act honestly and trustingly in the sense that the growth you can expect to experience in return depends exponentially on it.

The simulation works in the following way: a population consisting of a number of individuals undergo a number of transactions (iterations). Each individual is described by its capital, its honesty and its trust in each of the other individuals. Each transaction occurs between two randomly picked individuals A and B in the following way:

- A invests a value in B, where value = capital of A x trust between A and B.

- B generates some added value from the investment.

- a die is rolled and is compared to the honesty of B: B either returns the investment (successful transaction) or keeps the full investment (unsuccessful transaction).

- in case of a successful transaction, the trust between A and B is increased. Conversely it is decreased in case of an unsuccessful transaction.

- pick two new individuals A and B and go to 1 (unless the intended number of iterations has been reached)

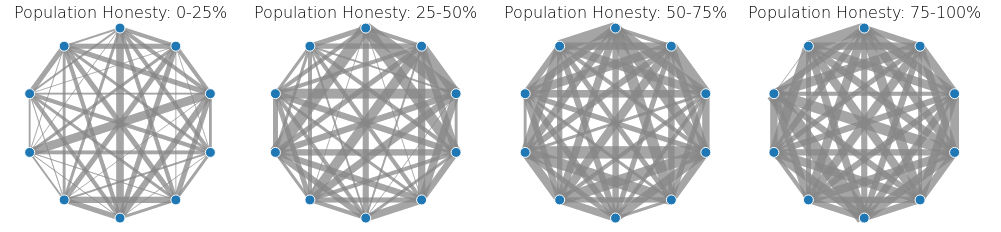

The resulting simulated relations of trust in a sample of four different populations look like this after 200 iterations (The thickness of the line expresses the trust score, between 0 and 1):

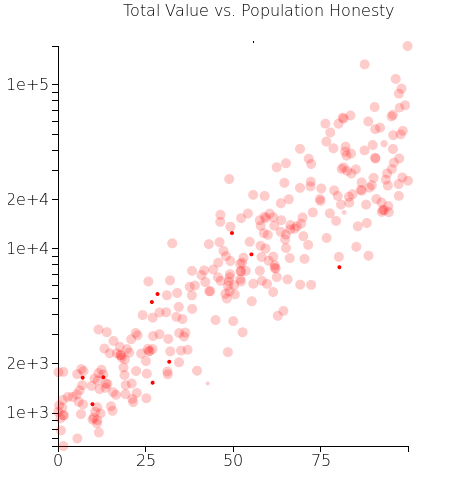

The corresponding simulated total value of the population looks like this:

That… is a semilog plot.

That… is a semilog plot.

It turned out that the y-axis had to be logarithmic to properly express how much of a winning strategy it is for a group of individuals to adopt an honest and trustful culture.

Conclusion

We have described that constructing trust amounts to building relations and how we do it. We emphasized the information-theoretic perspective, as we are uncovering that helping the children to condense the information, or understand, is a fantastic catalyst for trust.

We then saw that, perhaps surprisingly, growth depends exponentially on trust. Few other factors, if any, have that type of positive impact on society, suggesting that trust be the dearest treasure of any nation.